Origins of the Ranch, Part X

Deborah and her vital role in defining the “zest and surprise” of healthy food

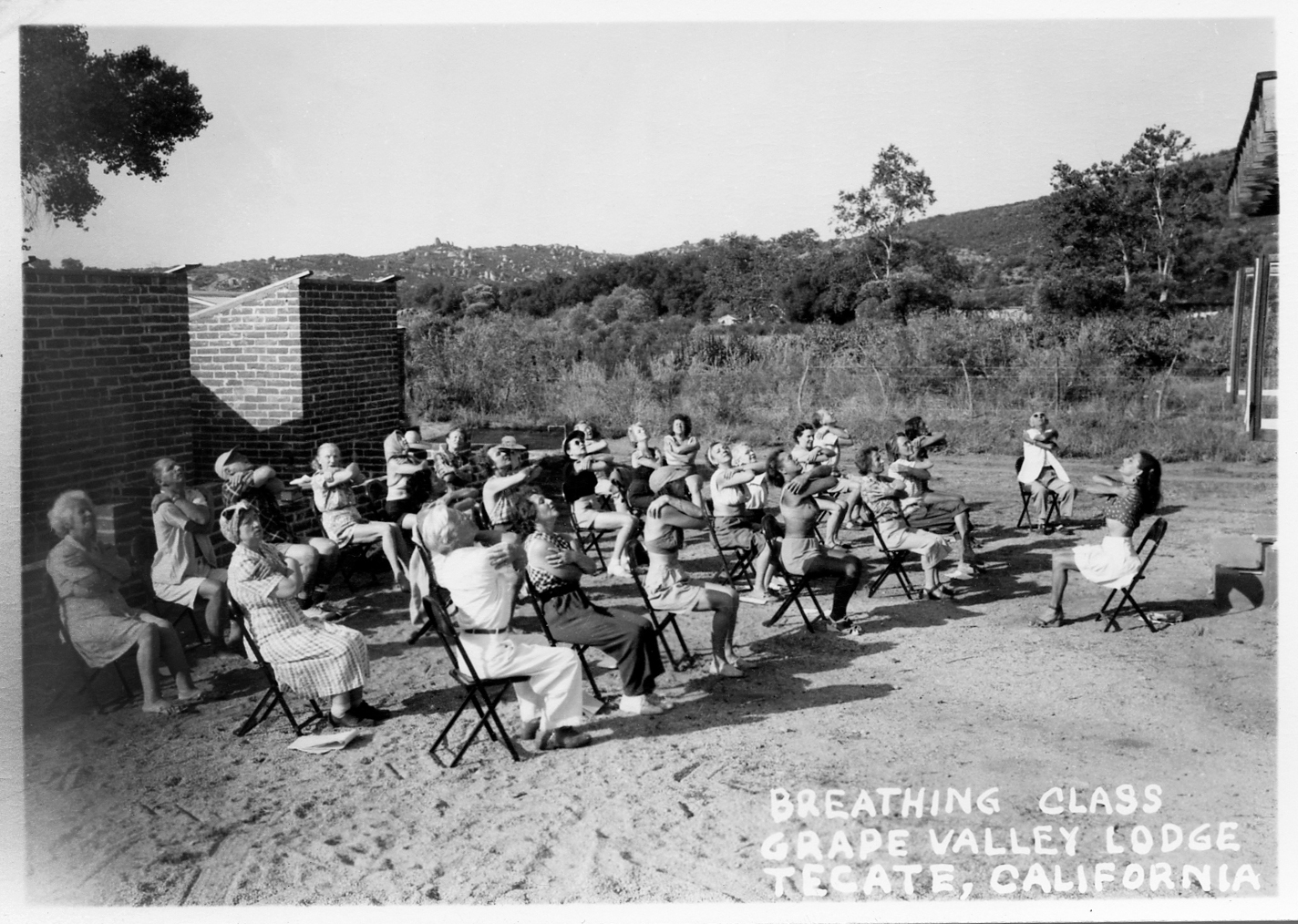

The history of Rancho La Puerta did not revolve entirely around food, but good, healthful foods played an important role from Day One in 1940. In this segment, based on interviews that took place in the 1980s, Deborah Szekely recalls the early days and what, for those days, were truly “Future Foods”—Rancho La Puerta style.

The Ranch garden and kitchen were always a crucial part of our work, and laborious work it was in those first years. Besides greeting the morning from a hilltop, part of our daily ritual included returning to the same hill to salute the evening star. Sometimes, some of us were understandably tired enough to bid the star hello from the bottom of the hill.

Among the important theories we were pushing so hard to establish was the one postulating that regional food is always the best, and that its nutritional value corresponds to the lapses of time and distance between the moment that fresh food is gathered and when it is transported, processed and finally eaten.

We cut down on time lapses by growing nearly all of our own food. We ruled out overcooking. Vegetables we served al dente or raw. The Professor particularly delighted in providing guests with the varieties now popularly called cruciferous.

“I am a great believer in the noisy vegetables,” he would say. “People chew them and think they are having a big meal, but it is all noise and fibrous roughage.” Such chewing is also tension-reducing.

In June of 1940, readying for our opening as a guest resort, our first purchase from very limited funds was a goat for cheese. Second, a bag of soybeans and a bag of wheat from Mr. Vandercook, the elder, who was descended from generations of Dutch millers and founded El Molino Mills in Alhambra, California, in 1926. He was a pioneer in the revival of stone ground flours.

Then we bought seeds and set out the West Coast’s first commercial organic vegetable garden. It wasn’t long before our friend Mr. Jerome Rodale, who went on to found Prevention and Organic Gardening magazines, stopped by to look over our planting. He was already talking about organic gardening, but we were doing it.

We consumed so many bean sprouts—customarily inserting five or six different kinds of sprouted greens into every salad—that eventually we designated an entire room just for sprouting.

We prepared tofu, then known as bean curd. We sun-dried our own fruit on chicken-wire racks in the old-fashioned way. For produce we had to save for winter months, we chose the cold-pack system. That first year, we canned 245 quarts of fruit with honey. You couldn’t tell that we had substituted honey for sugar, except that our fruit was more flavorful because of it.

The honey came from wild bees. Every day our guests would keep an eye out for hives in the rocks, and some of them (or a local beekeeper) would smoke out the bees and seize their honey. As civilization encroached on the wilderness around us, the Professor always specified sage honey as the most desirable. Other types, he knew, might come from bees with little discrimination that had strayed into fields subject to poisonous sprays. But, in the Professor’s words, “No idiot is going to spray sagebrush.”

As we acquired acreage and our number of guests inclined to chase honey declined, we created our own hives. At no time did we buy commercial honey because of the Professor’s worry that the bees would have been fed a syrup made from white sugar. Such bees he called “misled—taking in no minerals or vitamins and thus being unable to produce them.”

Although we grew our own sunflower seeds and dried them, we did purchase nuts. We kept them stored in their little suits and shelled them only as necessary.

In the Imperial Valley, we contacted a Hungarian grower who assured us that his dates were unsulfured. We bought a truck-load from him once a year.

Another importation came all the way from the Pasteur Institute in Paris: one pint of acidophilus culture. Although Man had consumed yogurt for over 4,000 years, it was then almost a total stranger to the North American continent, which knew even less about acidophilus. The Professor considered it far superior to yogurt. Our single pint of acidophilus multiplied so quickly that the Mexican workers, struck by its proliferation, called the culture los Bebitos (the little babies). We supplied other health resorts, some as far away as Canada, with acidophilus starters.

Next month: famous Ranch whole-wheat bread and the early “salad days.”