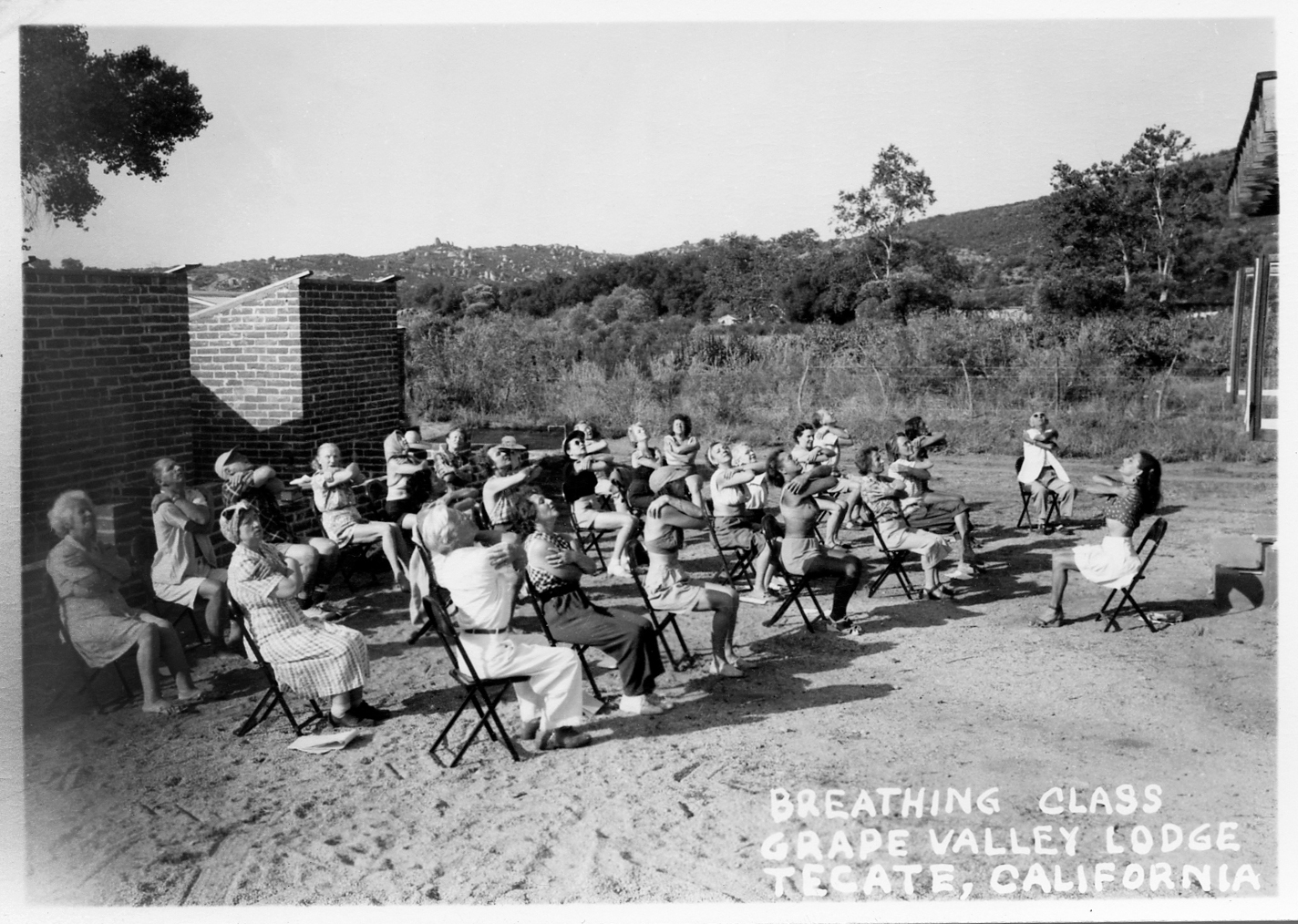

Origins of the Ranch, Part XX

A brief journey into “Cosmos, Man and Society”—some of the fascinating underpinnings of Rancho La Puerta’s “pre-Ranch” beginnings

Rancho La Puerta does not ask a guest to become a scholar upon every visit, but the opportunity is there. Just as a young English lawyer named Purcell Weaver was first drawn to the ideas of Ranch co-founder Edmond Bordeaux Szekely in 1934, it is possible today to delve back … far back to the earliest days…once you arrive at Rancho La Puerta.

The first and easiest way to do this involves walking around the main swimming pool, past a shady enclosure for hammocks, and walking up a curved brick path for a visit to Rancho La Puerta’s “museum,” which is the adobe house where Edmond and Deborah first lived.

The house is a fascinating combination of exhibits, as well as a recreation of what life in the 1940s was like for the couple. Furnishings give an inkling of that early and very rustic existence, while the walls are filled with photographs and a display of many of the Professor’s writings—small booklets, most of them examinations of early wisdom-teachings by ancient societies such as the Essenes, and Zoroastrians—and also the achievements over many years of Deborah Szekely, who not only built the Ranch into what it is today, but has had a remarkable life of philanthropy, volunteerism, and economic development in the U.S. and Latin America, particularly via her position for half a decade as the President of the Inter-American Foundation (IAF) in Washington, D.C., an independent U.S. government agency that channels develop assistance directly to the organized poor in Latin America.

Back to Edmond Szekely…

A new book about “The Professor” (guests gave him this moniker) is in the works from his daughter, Sarah Livia Brightwood, and it will do much to put in context some of her father’s writings, philosophy, and foresight.

Until that publication is finished, one can wander over to the current Rancho La Puerta library, which is about as extensive as any small community library. Look for a copy of “Cosmos, Man and Society”—a book dictated by the Professor in French when he was in Tahiti, and translated by Purcell Weaver, who happened to be in Tahiti at the same time (1934). (For more details, beyond what follows below, from the Tahiti years, see Origins of the Ranch parts I and II.)

Opening its pages, you enter a mind and an era that few vacationers at the Ranch take the time to be aware of. It is a dense and complex book, at times easy to understand via its common sense, and in other sections archaic and baffling because of the Professor’s liberal use of terms from his archeologic, anthropologic, philosophic, theosophic vocabulary mostly unfamiliar to us. Open the first few pages and words such as heliolithic, pan-harmony, omnilateral aristology (paneubiotics), and macrobiotes make the reader pause… But stick with it and soon his theories on toxins and diet are clear, with 800-plus pages to go.

Weaver, who lived into his 90s, visited Rancho La Puerta many times over his lifetime. One week he was asked to give a talk about the “early days” to the guests, and someone had the foresight to turn on a tape recorder. Here’s a brief excerpt. You can almost hear and see this distinguished, lean, adventurous (now elderly) man standing in front of his audience in one of the gymnasiums after dinner:

“When I arrived [in Tahiti] I behaved like a tourist and started round the island on a bicycle. When I got to the furthest end, a peninsula, I found myself in a little hotel. And there was an aged Englishwoman, or so she seemed to me because I was then 25, who instead of eating the good foods that the French hotel provided, spent all her day prancing up and down waist-deep in a stream doing an eternal fandango, and at meals—instead of the good food—she had just a glass of that white fluid that you see at lunch and breakfast sometimes [in Tahiti], and a little piece of papaya…or something like that.

“The English are notoriously reticent about asking people’s business. But, you know, you relax a little bit at the end of the earth so after a couple of days I found out what her name was: Lady Hatfield. And I said, ‘Lady Hatfield, I am fascinated by what you are doing.’ And she said, ‘Well, how old do you think I am, Mr. Weaver?’ So I cautiously looked her up and down and said, ‘I think about 50,’ and she said, ‘I’m 72!’ To which I replied, ‘I feel like 72, but I’m 25. What’s the secret?’

She said, ‘Well, there’s a man named Szekely back in Papeete who is doing medical work among the natives and also anybody else who comes along and wants his advice on health.’ So I said, ‘Sounds just the man for me,’ and I pedaled back to Papeete.

“It was rather a cumbrous business finding out where he lived, but I located him in the house of the mayor. One day I went out on my bicycle and had a talk with him. I had been rather ill for some years back in England and that was really why I was in the South Seas—to avoid an operation.

“So I met this man. There he was, a stocky, well-built man sitting at a little table. And he said, ‘Monsieur Weaver?’ and we had to talk in French because I knew no Hungarian, which is his native tongue, and he at that time knew no English. ‘What do you want?’ And I told him that this lady—Lady Hatfield—had recommended me to come and talk to him. And he, after a little general conversation, said, ‘Well, you deserve to be ill. For 25 years you’ve been doing all the wrong things.’”

Next month: more from Purcell Weaver’s lecture…