Origins of the Ranch, Part XXXVII

Eat Hearty!

A brief journey through The Ranch’s food history…with Deborah

By Peter Jensen

If you’re a regular reader of our newsletters, I’m sure you’ve heard the story of our earliest days:

When my husband Edmond Szekely and I started Rancho La Puerta in June, 1940, we put out the word to our first guests that their packing list of personal items was rather simple.

“Bring your own tent,” we said, along with light clothing, some good walking shoes, a bathing suit, and $17.50 a week.

We promised to provide the food, miles of challenging hiking trails on a beautiful mountain, a river to bathe in, and daily afternoon lectures by Edmond, who was already well-known to our first guests as the author of the book “Cosmos, Man and Society”—a manifesto of healthy living—and the leader of several prior health camps in places ranging from Lake Elsinore to Tamaulipas, Mexico.

Ah yes, the food: that was my department, along with everything else operational. I was barely 18 years old, but thanks to an upbringing as a vegetarian (my mother was vice-president of the New York City Vegetarian Society) as well as living in primitive conditions for five years on a beach in Tahiti I could cook, and do it over a wood-fired stove no less.

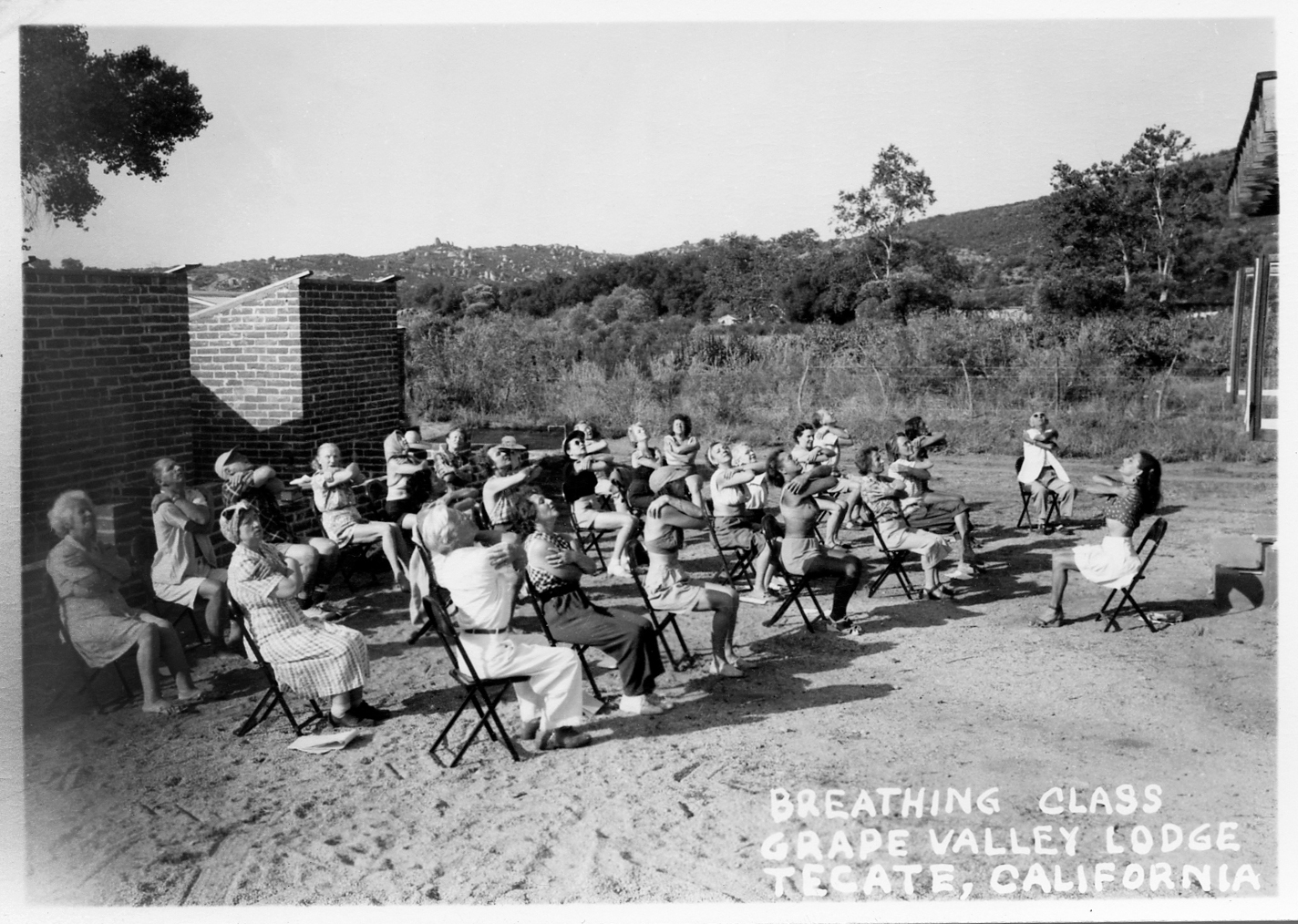

In our own way, we were slow food pioneers. Produce was raw and freshly picked. For lunch, we served a raw vegetable, a mound of cottage cheese made from our own goats’ milk, and little hard bun of sprouted wheat that we ground in an old hand-operated meat grinder, then baked in a beehive oven—or made into super-thin crackers we baked in the sun. (You can still see one of these cracker-drying boards atop a post behind my head in the photograph above this story.)

We planted a vegetable garden the first day. The ground was like cement. We didn’t have the money to hire local people, so one of Edmond’s friends, Bud Schroeder, did the first one. The guests worked in it as well, and I soon became a good administrator because I had to make people (who didn’t think they had to work) work.

Everyone had their own pot, which they washed themselves and left between meals in a cubby mounted near the kitchen. After getting their serving, most wandered off to find a quiet place to eat a “silent meal” alone under a tree or sitting atop a boulder. Others sat at a communal table.

We always had different kinds of bean dishes: pinto beans, of course, but also lima beans, which I am still very fond of. Dinner was lightly steamed vegetables. We made a rather elegant imitation-beef stroganoff (Hain made little patties of “meat” that I cut into strips). Ravioli was another favorite.

Nothing was processed or “fast,” and everything was pesticide-free and as fresh as possible. During those early years I’d drive into San Diego in a surplus Army Jeep towing a little trailer and buy sacks of beans, potatoes, onions, and, in winter, carrots…all for about $30. Along with our own goat milk we served local honey and vegetables that came out of garden, as much as you wanted. I was able to feed 20 to 30 people.

As time passed, more guests came, facilities were built, and small cabins dotted the landscape, each made from a war-surplus packing crate that once held an aircraft engine. They were just large enough for a cot. The guests were expecting better food, so we hired a cook: our first was Sam Demetrio, a Greek fisherman who occasionally would chase the Mexican ladies out of the kitchen while brandishing a big knife—and they scattered like chickens. A moment later all was forgiven. He was the classic temperamental chef.

Word about us spread. Health nuts knew about us. They came from New York City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Our food, usually eaten outdoors in all seasons (after all, we have the same weather as San Diego) had real “life” in it—plucked fresh from the ground or tree.

I firmly believe that any spa that has the opportunity to serve food has an opportunity to be a teacher. We are the healers of antiquity. People come because they are open, vulnerable, ready for a healthy change in their lifestyle, ready to take the responsibility necessary to prevent disease. All this knowledge is accessible; none of it magical. You are what you eat—it’s still as simple as that.