Origins of the Ranch, Part VI

The year was 1935…and even then the Professor’s bread was good. Very good. And so, too, were the “good radiations.”

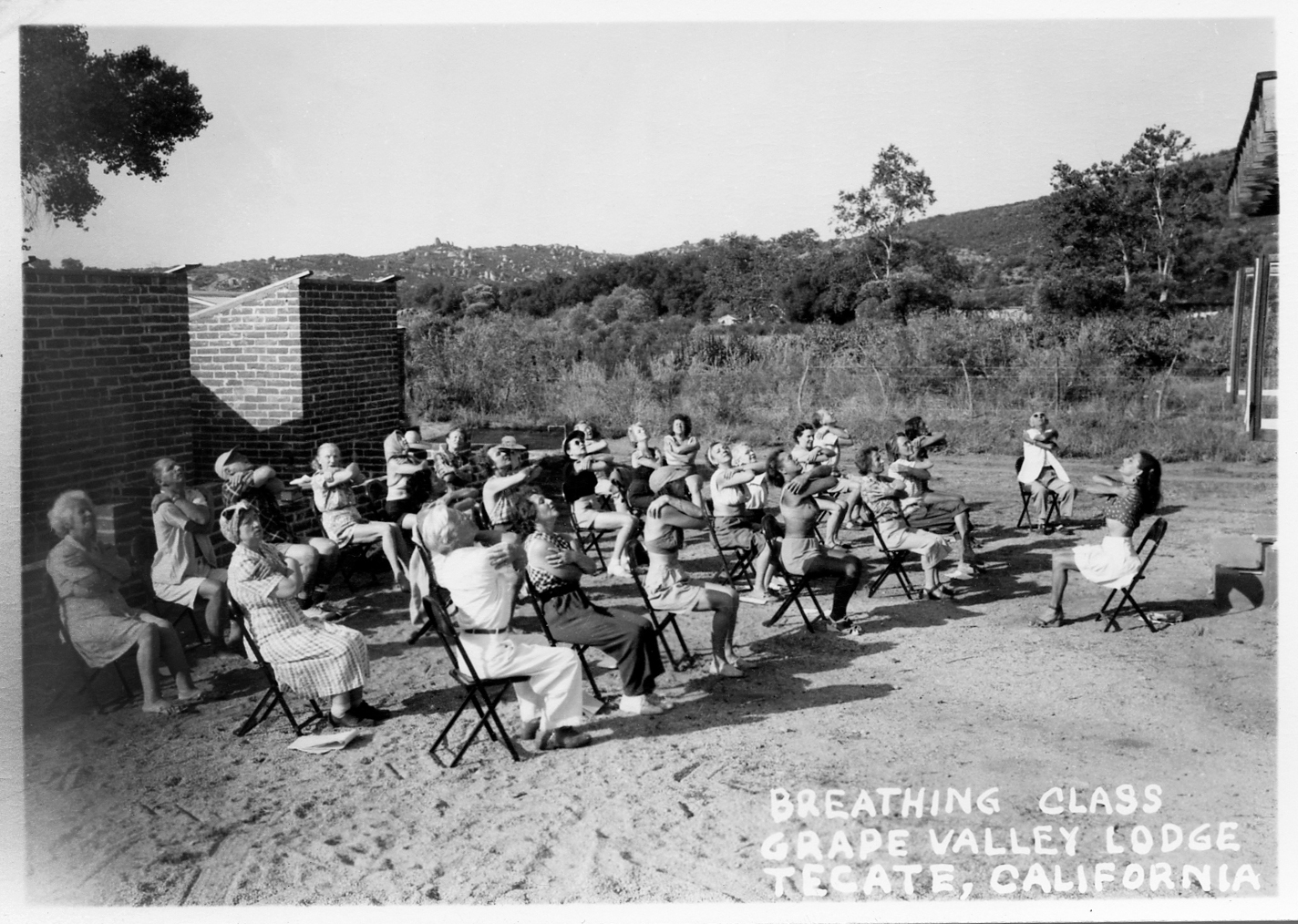

Englishwoman Florence Mahon’s recounting of her seven-month journey to “The Cure” continues; the setting a camp at Lake Elsinore, California—five years before the founding of Rancho La Puerta. Health innovator Edmond Szekely led a small group of English expatriates, all suffering from various illnesses, through a rigorous program that included fasting and exercise. Their will power and determination seems almost other-worldly today. Once “cleansed” of impurities, the group begins to eat bread and other foods again…and the results are remarkable.

During this period the diet changed to that of a building-up diet. For six weeks we had at midday one pint of fresh skimmed milk and eight ounces of homemade bread (whole-wheat) made with sun-radiated water only. The sun was so hot that we could bake our bread on the roof—after rolling out the dough till it resembled a thin wafer biscuit.

I cannot describe the joy of tasting this bread after four month’s abstinence; no cake or anything I could recollect tasted as good as this. What had happened was that through this cleanup I had got rid of all unnatural desires for food and appreciated the natural and simple foods. The bread had to be masticated well and the milk eaten with a teaspoon. Patience is needed here, for when one is famished it is a temptation to have a good drink and eat quickly. However, we got over that problem and found great benefit from observing this rule. We had the same amount of bread and milk again in the evening, but on alternate days we had fruit at midday and salad in the evening.

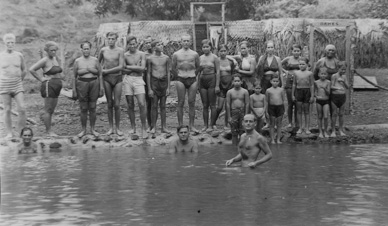

During this period the Professor explained that the bread and milk would help us build up muscle if we continued and even increased the exercises. We had to watch our weight and guard against putting on too much—aiming at a slow increase. We had not done much walking up to now, having saved our energy for exercises, but during this period we experienced the joy of walking and were able to increase the length of our walk daily. We did more swimming and in general more of the things that help for development of the whole body.

During the whole of the seven months we did not taste butter, cakes of any kind, pulses (the edible seeds of certain leguminous plants, as peas, beans, or lentils), cheese or nuts. We took no drinks, except, of course, fruit drinks in place of a meal. We increased the dried fruit during the last months and had bread with the salad meal in the evening.

A diet chart was given to us to use on our return home. This diet consisted of fresh and dried fruit, and nuts, sour milk occasionally, cereals for lunch, and salad and potato or bread plus home-made cottage cheese for supper. If we felt the need we could have steamed vegetables twice a week.

During the last few months we went to Hollywood and other places of interest, including several museums. We had picnics in the loveliest spots of California, and one especial thing I shall always remember was the journey to Hollywood Bowl to hear the Ninth Symphony of Beethoven. It was a starlit night, and in the Bowl (which is cut out of the rocks and very high up) we felt that if we stretched hard enough we should touch the stars. On the day previous to leaving California, Purcell and the Professor organized a day in an Indian Reservation camp. Szekely made a polenta dish, Purcell made a salad, and a Tahitian friend brought along the largest and juiciest melon we had ever seen. The two children we had with us—one my daughter June, and Mary, a little friend—found great joy paddling along the little streamlets with Purcell chasing them and having great fun. We sang songs, and the day will always be one to recollect with very pleasant memories.

During the whole period, Purcell did the hard work of shopping, organizing, and generally seeing to the welfare of all the patients. Nothing was too much trouble for him, and he would spend many an hour to make the children happy. During this time he worked on compiling “Cosmos, Man and Society” for the English edition. He did every bit of translating for the evening lectures, and for all the patients when they wanted to talk to Szekely. It was more than gratitude one felt for Purcell.

It will interest you to know that when I came home I went to see the practitioner whom I had been under for some time. He was amazed at the change. Not only had my general condition improved, but, among other things, a badly perforated ear-drum had healed. That same afternoon he was lecturing to students, and asked me to go along with him and give a brief outline of all that had happened. This I did, and the students asked for tests, to which I submitted, and they found that all I claimed had been justified. A thing that held their attention was the fact that my vaccination mark, which I had when I was a baby, was raised up and forming a scab, so proving the theory that during the cure one retrogressively goes through the various complaints and diseases back to the date of birth. They had come out one by one, and I was on the earliest one—that of vaccination.

The contrast in my condition before and after was more than amazing. Before the cure, I could not walk up a flight of stairs without having to sit in a chair for a very long time afterwards—could not go into a shop without forgetting what I wanted (even the simplest things, and perhaps only one item)—always in pain and depressed.

Now I knew nothing of these things and enjoyed every moment of life to the fullest.

I can honestly say that Szekely practiced what he preached. He gave out love, or as some would have it, “good radiations,” at all times. Never once did he show any signs of irritability or lose patience with us (as I am sure he was often entitled to have done), but all the time he was ready to talk and explain and give help in every way possible, and to reassure us when we were depressed.

I expressed my heartfelt gratitude to Edmond Szekely and Purcell Weaver [by carrying] the good news of hope to all those who were suffering, and also to show, if possible, to those who were enjoying comparative good health, that disease and unhappiness could be avoided.

Next month: The “Cosmovitalist” advises on “Health and the Daily Dozen.”