Origins of the Ranch, Part XXX

Deborah’s Fond Memories of A Honey Heaven On A Sacred Mountain

By Peter Jensen

Giant granite boulders on the mountainside almost vibrated with the thrum of a million wings. Deep in the rock crevasses, workers toiled mightily to mine the golden nectar of an entire mountainside’s pollen-rich sage. The sanctuaries were protected from all predators, except for two wily Mexican men who knew the secrets of the wild hives…

“We needed about 100 gallons of honey a year,” recalled Deborah, when we spoke with her recently about honey not only because it is considered by many to be a near-perfect natural food, but is also at the heart of worldwide concerns about the declining populations of “pollinators” such as bees, bats and butterflies.

“During our early years, from 1940 until the ‘50s or perhaps even later, we relied on wild honey gathered by two Mexican foragers who knew the ways of the bees on the mountainside above our health camp about 45 miles southeast of San Diego in Tecate.

“The bees preferred the same crevasse homes year after year,” Deborah continued. “The local men knew the terrain well, and they would arrive in our camp on horseback, laden with 5-gallon cans of honey gathered from the mountainside hives. It was thick and dark, with a very strong wild sage flavor.

“We used most of the honey for a healthful grape juice drink made for our guests—a kind of grape cider that was vinegary and needed some sweetening. Today vinegars like Bragg’s are still widely recognized as a healthful tonic. Our ‘grape cure’ was very popular, especially on hot summer days.

“Another experiment with the honey went amiss because of its strong flavor. After a good harvest of apricots and peaches, I canned 280 quarts of fruit. They all tasted alike! It was a disaster—the honey flavor overwhelmed the fruit completely.”

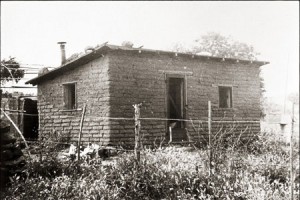

“One summer after World War II,” she said, “We tried to go into beekeeping on our own. It seemed like a good business to start on a parcel of rancho land we owned. The land had to be productive agriculturally; otherwise it might be taken over by homesteaders. Beekeeping sounded … not simple, but better than raising cattle. We bought cans, a separator—all the necessary gear.

“One long night, we had a trucker leave Arizona with a load of 20 double hives we’d purchased. He drove straight to Tecate so he could cross the border before dawn. It was a simple way to let the bees sleep through the night, and wake up the next day in their new home.

“All went well at first. We’d even built a 1-inch-deep pond of water and floated wood strips of lath so the bees could land and drink. But by the end of the first week, the hives had been invaded by aggressive wild bees and all the Arizona stock had been chased away or killed. One would probably call those invaders ‘African bees’ today—and they were impossible to domesticate easily. We were out of the beekeeping business as fast as we were in it!”

The rocks still hold their golden troves, but few know where anymore. The old honey men are gone. Today the region’s honey comes mostly from hives. And yet… one can occasionally still see a battered car parked alongside the road between Tecate and Rancho La Puerta, and atop the car’s faded metal roof, the brilliant cylindrical-bottle gems glow in the sunlight, waiting for someone to stop and buy a pint or two of the sage-y, strong nectar. Sometimes, deep in the amber, you’ll spot a bee wing or leg, proof that the old ways of gathering honey from the wild are still known to a few.